Introduction

The liver is the most commonly injured organ in blunt abdominal trauma [1]. Over the past 3 decades there has been a clear shift toward non-operative management (NOM) of liver trauma as a safe and effective treatment for many low and high grade injuries [2]. As the severity of liver injury increases, so too does the risk of complications. We present a case of high grade liver injury following blunt abdominal trauma, complicated by hemorrhages, bile leaks, and recurrent infection causing prolonged hospitalization. We propose that early operative intervention may prevent such complications in some cases of liver trauma.

Case Report

A 21-year-old, otherwise healthy male, was brought to a Level 1 trauma center, following a high speed motorbike accident. He had worn a full-face helmet but no other protective clothing. On arrival to hospital, he was peri-arrest with a Glasgow coma score 6 (E1V1M4). He had closed midshaft humeral fractures with neurovascular compromise bilaterally. A Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma scan was grossly positive with fluid in 4 quadrants. The Massive Transfusion Protocol was activated, although he remained hypotensive despite resuscitation. He was transferred directly to the operating theatre for a trauma laparotomy.

Operative findings included a Grade 4 liver injury between Segments 6 and 7, a non-expanding Zone 1, and right Zone 2 retroperitoneal hematoma, with a normal stomach, spleen, bowel, and mesentery. Packs were placed around the liver and a Vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) dressing was placed for temporary abdominal closure.

A subsequent computerized tomography (CT) Trauma Pan scan showed a large retroperitoneal hematoma with active bleeding on the right from the adrenal artery. He underwent right adrenal artery coil embolization and had to return to the operating theatre for a laparostomy because there was re-accumulation of hemoperitoneum. Ongoing bleeding from the liver was observed in Segment 8 and lesser sac, therefore, the liver was re-packed. The retroperitoneum was not explored. A 2nd interventional radiology procedure led to identifying the need for embolization of the right hepatic arteries at Segments 7 and 8, as well as coil embolization of the right renal artery. Ultimately the Massive Transfusion Protocol resulted in 97 units of blood products being used prior to his arrival in intensive care.

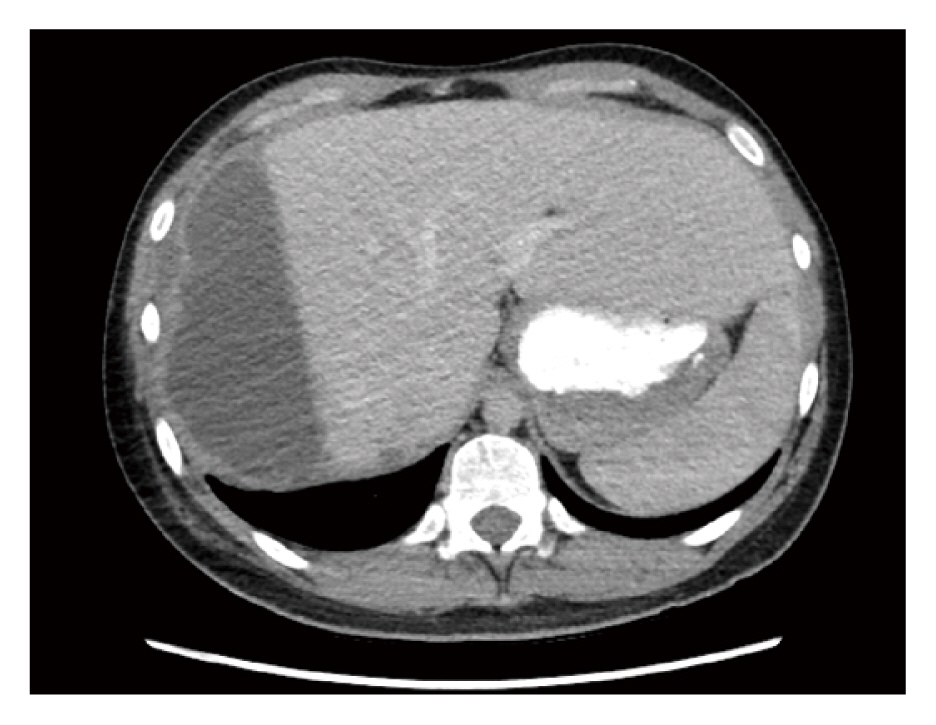

The liver was re-packed on Day 3 post injury, and on Day 5 all packs were removed and a VAC dressing was used because it was not possible to close the abdomen. On Day 18, bilious output was observed in the VAC dressing, so the patient was returned to theatre where a bile leak from the liver was confirmed (Figure 1). Two suprahepatic Jackson-Pratt drains were placed in an attempt to control the leak. The following day, 1.2 L of bile had drained from a right sided pleural effusion, indicating a right sided diaphragmatic injury. A further laparostomy was performed, and the diaphragmatic injury was identified and repaired, following this procedure bile drainage escalated from both abdominal drains and the VAC dressing. He underwent an Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with sphincterotomy and placement of a 9 French plastic biliary stent (Figure 2). The bile leak persisted at Segment 7 as observed on the CT Cholangiogram scan a week later. The bile leak was managed conservatively, and the patient was discharged on Day 48 post injury with ongoing significant bile output from 2 drain tubes in situ.

There were subsequently 2 re-admissions for infected perihepatic collections. The 1st was 2 months post discharge (4 months post injury) with escalating abdominal pain, which was managed with an ERCP, and the plastic biliary stent was exchanged for a fully covered metal stent (10 mm ├Ś 4 cm). This improved the size of both the perihepatic collection and persistent central biloma identified on the readmission CT scan (Figure 3). Two months later, the metal stent was removed without immediate complication.

Over a year post injury, the patient returned presenting with fever and escalating abdominal pain. A recurrent large perihepatic collection, identified on the CT scan, was managed with ultrasound guided drainage (Figure 4). The infected bile was drained and he was discharged home 6 days later with resolution of symptoms. At subsequent follow ups at 2 weeks, 4 months, and then at 2 years following this 2nd readmission, the patient remained well with no further issues related to bile leaks or abscesses.

Discussion

In the majority of patients with low or high grade liver injuries, who are hemodynamically stable and who do not require abdominal exploration for other reasons, NOM has been demonstrated over the past 3 decades as a safe and effective treatment [2]. However, in patients managed with intervention, the risk of complications increase. It is unclear whether this is either due to the surgical intervention per se [laparotomy, liver packing, angioembolization (AE)], as a result of the injury itself, or a combination of both [3].

The risk of a bile leak increases as the severity of liver injury increases. The risk of a bile leak in low grade liver injury (i.e., Grades 1ŌĆō2) has been reported as low as 0% [4ŌĆō8], whereas in high grade liver injury (3ŌĆō5) the risk of a bile leak has been reported as between 4.7ŌĆō25% [4ŌĆō9]. Often the initial identification of a bile leak is delayed, ranging from 5 days to 22 days post admission [3,7,10]. The reasons for this include biliary ischemia following AE, and a delayed leak through to the rupture of the subcapsular collection of bile. Once diagnosed, a bile leak significantly increases the length of hospital stay [9].

The management of bile leaks that are enlarging, symptomatic, or infected are less likely to be successfully managed with NOM. An ERCP with sphincterotomy and stenting is a widely utilized adjunct tool available for major bile leaks [10ŌĆō13], because it theoretically reduces intra-biliary pressure to allow defects to close spontaneously. A laparoscopy may be also indicated in these situations to facilitate peritoneal lavage and drainage, potentially avoiding the need for a laparotomy [14].

An ERCP with stenting is a widely accepted treatment for bile leakage following trauma, with many surgeons advocating for it to be a 1st line intervention when a bile leak is diagnosed. Multiple studies report up to 100% success rates in resolving bile leaks, however these studies likely had too few patients or potentially included bile leaks that would have closed spontaneously [3,11ŌĆō13,15]. Few reports have discussed the risks or pitfalls to ERCPs [16]. In a retrospective study of blunt liver trauma in 639 patients (July 2010 to December 2019) at the Alfred Health, Department of General Surgery, Melbourne, bile leaks accounted for almost 5% of cases, and the resolution of bile leakage without the need for intervention was successful in 42% of those patients (n = 31), compared with major morbidity related to ERCPs (28%, n = 18) [17]. Therefore, ERCPs at the Alfred Health are typically performed in patients who fail conservative management of bile leaks following blunt liver trauma.

Herein we describe a case where an ERCP was not a helpful modality because the source of biloma was from a disconnected segment of liver therefore there was no drainage via the biliary tree. The ERCP itself may have potentially contributed to morbidity in this patient, with bacterial colonization of the devitalized liver occurring at time of instrumentation of the biliary tree via the gastrointestinal tract, preceding recurrent admissions with sepsis related to an infected biloma.

Ultimately, hepatic resection may be necessary to treat ongoing biliary fistulas, especially in the context of patients with segments of de-vascularized liver parenchyma [18], where injudicious ERCPs may lead to contamination of devitalized tissue, and subsequent liver abscesses further complicating intrahepatic bilomas. The role for hepatic resection in liver trauma management has been well described. The current frequency of liver resection in liver trauma is difficult to accurately ascertain, however, anatomical resection has previously been reported as 2ŌĆō4% in the 1990ŌĆÖs [19]. The indication for anatomical resection is primarily major devascularization and/or major ductal injury with an uncontrolled bile leak. Non-anatomical resectional debridement makes up a further unclear portion of resections, along the line of devitalized parenchyma rather than anatomical planes. In current practice, hepatic resection is often considered a last line of treatment following the failure of all other interventions. However, early identification of patients who are at high risk of failing NOM, such as described in this Case Report, may benefit from early hepatic resection, which may minimize a prolonged hospital stay, and potentially reduce additional procedures and complications. In this case, operative management was not considered early, which is in line with the current trend of opting for NOM wherever possible. However, this case could have been predicted as high risk for having a complicated clinical course.

In the acute setting, a trauma laparotomy for hemodynamically unstable liver injury focuses on damage control to restore hemostasis by using packing combined with hepatotomy, and selective ligation or hepatorrhaphy, rather than anatomical or non-anatomical resections, particularly in the initial phases [20]. AE has revolutionized the management of bleeding, minimizing the need for early resection in many cases. There are limited studies in contemporary literature advocating for early liver resection following liver trauma [9,21]. Current guidelines suggest resectional debridement in cases of large areas of devitalized liver tissue not at the index trauma laparotomy but at subsequent operations [18]. However, there is a time window for this opportunity, and months later it may not be possible to safely resect the injured liver that has sustained recurrent abscess drainage procedures, ongoing bile leaks, and major bleeding, especially when the zone of injury is the right posterior section (given its proximity to the inferior vena cava). In the described case, predictable complications began to declare relatively late in the clinical course, by which time the operative field was hostile, making resection a higher risk. This may provide further rationale for making an early proactive decision to resect devitalized parenchyma complicated by a bile leak which may result in improved outcomes in patients with injury patterns such as the case described herein.

Conclusion

The management of severe liver trauma complicated by a bile leak often requires an experienced multidisciplinary management team. Despite the widespread use of ERCPs in liver trauma cases, it needs to be clear that in some instances it not only has limited efficacy but also has the potential to cause harm. Warnings from the literature should be heeded about the risks of 1st line ERCP. In order to further assess the efficacy of ERCPs with sphincterotomies and endobiliary stenting in a variety of liver trauma cases, closer analysis of larger data sets is required. Analysis of national prospective data collection via a trauma registry-based project would allow assessment of the true value of ERCPs in bile leakage cases following blunt liver trauma. Surgeons should consider early liver resection in severe bile leaks associated with disconnected hepatic segments, or devitalized infected hepatic parenchyma such as in this case.